Los Angeles Seige of 1992

“The balance and scales of justice have their origin in ADONAI; all the weights in the bag are his doing” Proverbs 16:11

As we mark the 33rd anniversary of the Los Angeles Siege, which took place in April 1992 I am reposting an important article I wrote previously last year that reflects my experience of living the events surrounding the National Guard deployment and mobilization of the City of Angels.

Arriving in Los Angeles right after the 1992 Los Angeles Siege on April 30 of that year brings back to my mind vivid memories of a beautiful city I loved engulfed in complete chaos. I was in Spain finishing filming a Spanish TV series when the seige began as a reaction to the Rodney King beating by members of the LAPD. I landed in a nearly empty L.A., which was surreal in a city known for fun and vibrant energy. I left Los Angeles about a month earlier, but when I came back on April 30 I landed in a city unrecognizable and it’s electric dynamic energy was gone, replaced by an eerie silence, calling attention to the chaos and disorder displayed by the quiet of the curfews.

The devastation was staggering—over 50 deaths, thousands injured, and billions in damages. The still streets were ghostly reminders of the unrest and the deep-rooted issues affecting the community trust. After fetching our vehicle, I vividly remember, like it were yesterday, the convoy escorting us first to the only open fueling station near LAX, where we waited in line for about thirty minutes. I felt like I was in a war, and the presence of the military controlling my movement emphasized my sense of insecurity. The National Guard had been deployed by President George H.W. Bush, accentuating the tension in the air of The City of Angels. After gassing up, we followed our convoy to the LA/Orange County line where life went on as usual as we bid the military good bye. Let freedom reign.

As we mark the 33rd anniversary, it’s clear that an event this large shapes a city’s cultural future and influences the memories of those who experienced it. My reflections contribute to the LA Siege's history, reminding me it’s vital to keep these memories alive so the lessons from that tumultuous time aren’t forgotten.

This is the story I told last year in my article Magic Equilibrium, published in June 2024;

When faced with uncertainty fear naturally arises as people wrestle with the apprehension posed by volatile circumstances. The breakdown of law and order, the threat of violence, and the loss of safety can produce a primal sense of vulnerability and anxiety.

Confusion often accompanies such events as individuals try to make sense of the rapidity of the unfolding situation, especially when the violence erupts in a place that they have always considered peaceful.

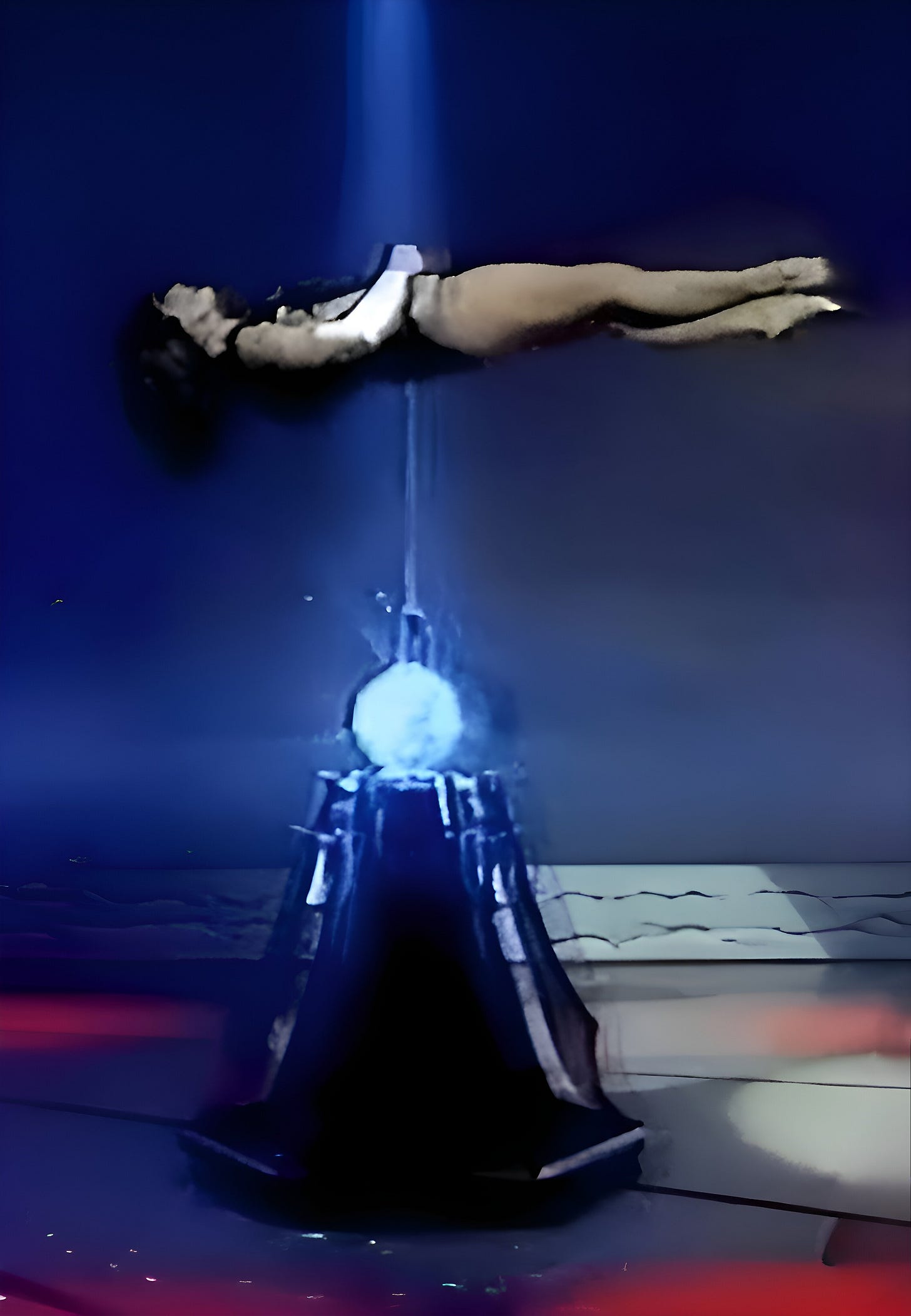

Balance of justice and magic? How do they relate? I asked myself about the power of magic has over justice in this world. I've noticed justice and righteousness can be seen in magic at the intersection of perception, deception, and fairness. Having the knowledge and ability to deceive and engineer perception on stage for entertainment purposes gives the manipulator real power. I can feel it flowing from the audience when I perform onstage. Then there’s magic that requires balance, which can be seen in The Pendragon’s performance of Impalement, and it was my role to balance. When I did it well, I was relaxed and at ease, perfectly balanced on the tip of the sword. I could lay there all day and never want to get down. Similarly its the feeling felt while floating on water. But once the balance was disturbed, I had to fight to keep from wobbling and kinetically worked hard physically to keep my position stabilized. I knew that perfect spot in my body where I could feel balanced and stable, and I tried to achieve that every time. It’s a force to reckon with when trying to perform magic. The same is true when the scale of justice is tipped. Sometimes, tipping causes wars to ignite. Only through restabilization and righteousness can there be peace and tranquility, and the scale returns to harmony.

Last week, I discussed a TV show I was featured in Spain. I performed on six of its segments. It was called Chan-tatachán. Intrigued by the name, and I was told Chan-tatachán is an informal Spanish term mimicking the sound of a drumroll, creating anticipation and emphasizing surprise in a performance. It embodies the thrill and suspense felt by audiences before a pivotal reveal. Like the familiar call of "The moment we've all been waiting for!" by a ringmaster, it heightens emotions like when a trapeze artist takes flight, holding our breath until they safely connect with their partner. It was the perfect name for the show starring Juan Tamariz, a famous Spanish magician who finished his routines with his enchanting invisible violin. It’s his Chan-tatachán moment. From a personal standpoint and unknown to me then, the show turned out to be a microcosm of a larger-scale event unwinding on the streets of Los Angeles, my destination after filming the series. A megaton Chan-tatachán moment. The final day on the set, a production assistant approached me, asking if I had seen the news about Los Angeles under siege. Not aware of the situation, I felt a wave of fear as I learned more. The Rodney King riots had spread to Hollywood and Long Beach, unbeknownst to me due to my focus on work in Spain. Despite declaring martial law in Los Angeles County the next day, our flight departed from Madrid towards the chaos.

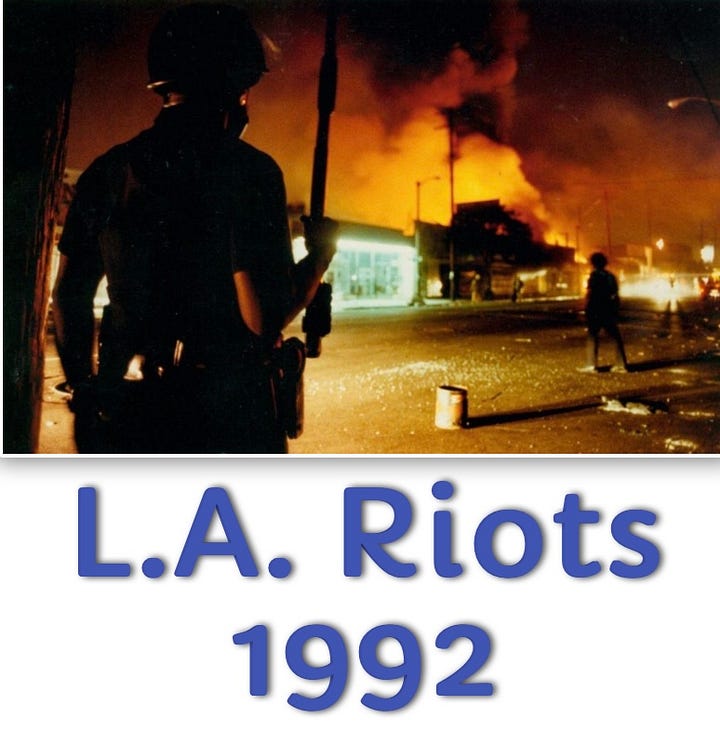

Not knowing the state of affairs was in Los Angeles in April 1992 was frustrating. It was a time before the internet was heavily used, so we had to rely on breaking news updates fed to us through Spanish TV, and a little International CNN. All channels covering the event showed a city engulfed in confusion and disorder. A war zone was shown with plumes of smoke rising from various parts of the city, especially in neighborhoods like South Central Los Angeles and as far away as Hollywood and threatening Beverly Hills. Occasionally, the news reports shifted to scenes in Long Beach, California, where much chaos could be happening. Visible were fires, burned-out buildings, and a general haze due to widespread arson and looting. I had to ask myself if this was Los Angeles and not Beirut. I was in a state of shock because this didn't happen in America. The emotional and psychological impact of witnessing this war zone in a once-tranquil Los Angeles was profound and unsettling. It stirred up a mixture of emotions in me as I watched the news. That day, I learned the fragility of peace and sudden upheaval that can occur anytime, anywhere, and most disconcerting, it can occur in seemingly secure environments. So my world was rocked along with everyone else witnessing the devastation and destruction, which shouldn't have ever been.

Have you ever seen how wasps react to disruptions? When a wasp nest is disturbed, the walls of the hive ignite with unity when the wasps mobilize to protect their home turf. Similarly, when the flames of war break out among people, a collective response brews. Like the wasps, people form a hive, and fear and anger are the fuel that unites them to respond viscerally to the aggression of perceived threats, mirroring the primal reactions of these flying insects when survival is at stake. That was pretty much how the Los Angeles Rodney King riots occurred. But why did they happen? What spark ignited such deep-rooted anger in specific population demographics? Most people believe the riots were simply a comeback by mostly the black population in South Central Los Angeles in response to the innocent verdict of the police officers on trial for beating Rodney King: justice and injustice. The Rodney King riots were all about justice and injustice and read like a Shakespeare play where this theme is often apparent in his works like Measure for Measure and Macbeth. Defining justice and injustice can be very thorny, and according to the dictionary, justice is defined as "the process or result of using laws to fairly judge and punish crimes and criminals" or "the quality of being just, impartial, or fair" (Merriam-Webster 2016b). Injustice, on the other hand, can be defined as "a situation in which the rights of a person or a group of people are ignored, "violation of right or the rights of another," "unfairness" or "wrong" (Merriam-Webster 2016a). Some of the characters in the Rodney King Shakespeare play believed their rights were ignored, triggering their hive reflex to respond accordingly, and they did, as the governor reacted by calling the National Guard to reestablish peace. So who are the players?

The main characters in this real-life Shakespearesque story were:

Soon Ja Du - A Korean–American store owner who shot and killed Latasha Harlins

Latasha Harlins - a 15-year-old Black girl

Rodney King

Sgt. Stacey Koon, Officer Laurence Powell, Timothy Wind, and Theodore Briseno. The four police officers who were charged with assault with a deadly weapon and using excessive force in the beating of Rodney King were later acquitted in the King trial.

Judge Joyce Karlin

Judge Stanley Weisberg

So here is the synopsis of the real-life drama:

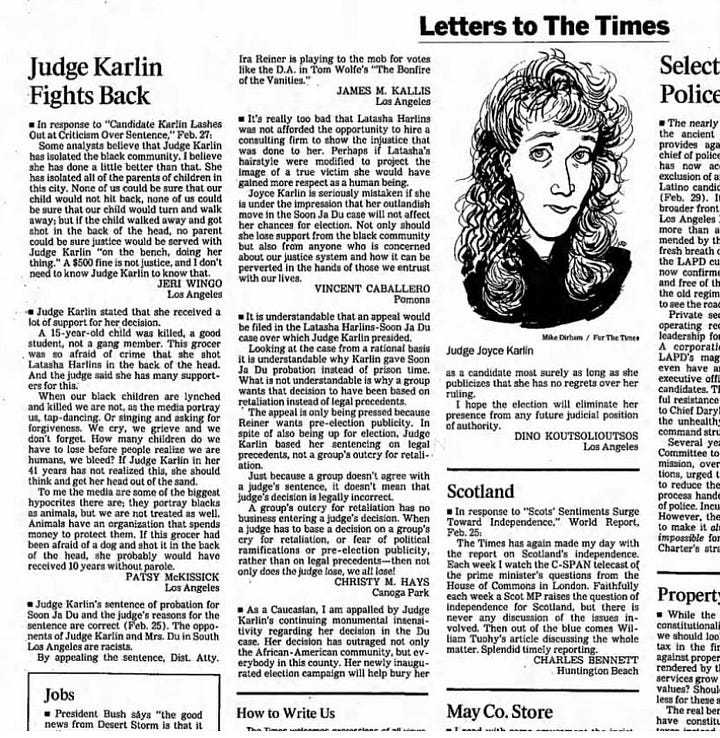

First up Soon, Ja Du, a Korean-American store owner, and Latasha Harlins, a 15-year-old Black girl. On March 16, 1991, Harlins entered Du's liquor store in South Central Los Angeles to buy a bottle of orange juice. A confrontation ensued, during which Du accused Harlins of attempting to steal the juice. After a physical altercation, Du shot Harlins in the back of the head as she was leaving the store, killing her instantly. Soon, Ja Du was charged with voluntary manslaughter. In her trial, she claimed self-defense, arguing that she believed her life was in danger during the confrontation. The jury found her guilty of voluntary manslaughter, which typically carries a maximum sentence of 16 years in prison. However, Judge Joyce Karlin sentenced Du to just five years of probation, 400 hours of community service, and a $500 fine without sentencing her to prison time. It was a highly controversial decision, sparking many comments sent to the Los Angeles Times. This lenient sentence exacerbated existing racial tensions in Los Angeles, most notably between the African-American and Korean-American communities. It was viewed as a horrible miscarriage of justice by many in the surrounding Black communities and contributed heavily to the broader sentiment of injustice and anger that fueled the Los Angeles riots following the Rodney King verdict, where four police officers, Sgt. Stacey Koon, Officer Laurence Powell, Timothy Wind, and Theodore Briseno were charged with assault with a deadly weapon and use of excessive force in the beating of King and were later acquitted by Judge Stanley Weisberg. The case of Latasha Harlins remained a poignant example of the racial and social inequalities widespread in Los Angeles during the time.

So the verdict of all four police officers is read in Judge Weisberg’s court: “NOT GUILTY!”

The next chapter goes something like this:

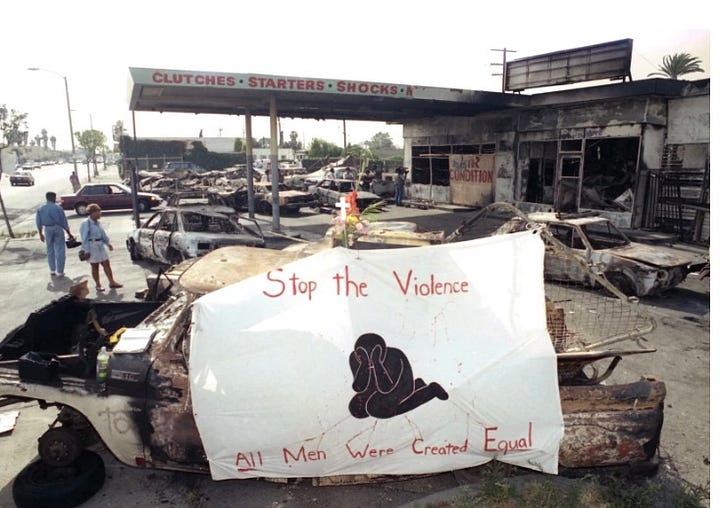

The angels in the City of Los Angeles, sat still under an April spring sky, while the people waited with bated breath as the verdict in the Rodney King trial was finally announced. Emotions were mixed as anticipation turned to joy and exoneration for some, and in others disbelief, then fury, as the words "not guilty" resounded through the courtroom. Outside, at the volatile, infamous intersection of Florence and Normandie Avenues, emotions boiled over like a pot left unattended on a blazing stove. It was here a white truck driver, Reginald Denny, was grabbed out of his vehicle and bashed by four black assailants with a brick and other objects. A crowd formed a seething mass of anger and disillusionment as the protestors erupted into chaos. The first stones flew, shattering windows and encouraging more revenge by the masses. Florence and Normandie became the crossroads where the spark lit the fuse of the first revolt that soon engulfed Los Angeles in a storm of violence and desperation.

The verdict stirred emotions to their breaking point, and what began as a cry for justice had descended into a maelstrom of violence and suffering. The riots spread like wildfire across the city, and the fire of unrest reached Koreatown, where Soon Ja Du killed Latasha Harkins. Businesses lining the streets in Koreatown became targets of the wrath consuming the city. Shattered glass and smoke-filled air were a grim testament to the turmoil gripping the once-vibrant friendly neighborhood. But their spirit of resilience emerged with determination and a fierce desire to protect their livelihoods. Banding together and forming impromptu defenses, they shielded their businesses from the tide of destruction coming their way.

They stood guard, and in unity, their hive was a beacon of strength as their resolve echoed through the streets—a testament to the power of their unity. When the dawn finally broke, Koreatown bore the scars of the war, but in the wake of devastation, a new dawn rose out of the burning ashes, as people began rebuilding their communities and repairing emotional wounds caused by the destruction. The hive started rebuilding itself, but not before California Governor Pete Wilson called the National Guard to help restore order in Los Angeles, a city grabbed in the unrest—tough decisions like that are the governor's responsibility. Wilson took immediate control of the situation, bringing Los Angeles to stability and showing with some gusto how a governor can quickly end war and destruction from city rioters. A lesson failed to be learned by governors in later years who failed to carry out plans to stop rioting in their states, and as a result, much devastation in American cities transpired. It serves as an ominous warning that if the balance of justice is out of alignment, people's communities will react and arise accordingly. Exactly like when I balance on the tip of a sword, and something is not right, I have to re-stabilize my body by adjusting to balance again. I will begin to wobble if I am not in that perfect spot. And a wasp is at peace unless its tranquility is disturbed.

Looking at Los Angeles at night from an airplane was always a breathtaking experience giving me a unique perspective on the sprawling metropolis, which extends as far as the eye can see. A vast expanse of glow stretches out in all directions below you. It appears like a shimmering sea of lights against the dark backdrop of the night sky. If you look around, you see the grid-like pattern of the streets below, and you can even make out a few noticeable ones like the freeways with a solid line of red lights going in one direction and white lights traveling the opposite way. You also see the iconic landmarks such as the downtown skyscrapers, the Hollywood sign, and the Dodger Stadium lit up like a city of itself when the Dodgers play home games. So, on May 1, 1992, I looked out my window at the cityscape, searching below for evidence of the riots. None I could see, but the quietness of the usual bustling city was creepily disturbing. I could see none of the moving cars on the highway. No action. No movement. Just stillness is below as the pilot gave us instructions after disembarking the plane.

I left the flight, stepping into an abyss of the unknown. It wasn’t long before I noticed the airport was under heavy security, with the increased presence of police and National Guard troops. So we were instructed to gather our bags and car from Lot C, proceed out the gate, and wait for the National Guard to escort us out of the airport. We needed gas, so that was an extra issue. Our usual routine was to purchase gas as we drove out of the airport, but this would not happen tonight. I spoke with one of the Guardsman, and we were advised to wait for a National Guard to escort us to one of the few gas stations open in Los County. It was located in Santa Monica and we feared we wouldn’t make it, but we did. So, leaving Lot C, we entered a convoy with about 20 cars and drove to Santa Monica for gas. Once we were all gassed up, we all divided into groups depending on our destination, and a second National Guard shepherded us to the Orange County border about 40 miles away. When he turned to go back, we entered a much livelier Orange County where residents were out evening shopping and eating. The freeways were full of life. It was a complete dichotomy comparing OC to LA, which, at that time, was still lifeless. I will never forget the feeling I had leaving the dead zone of Los Angeles County and entering the living zone of Orange County. I felt magic in the air. I experienced the dark invitation of chaos while also sensing the unique enchantment from “order” and the organization of the life force energy surrounding us. The structure. The stability. The method. Those things that are opposite disorder. That’s the magical energy I seek and understand. Some people follow a deceitful spiritual familiar, and that power draws them to the falsehood of darkness. Other people find the magic of the light. Those folks can easily balance on the tip of a sword.They see the balance of justice. Ask yourself, what kind of magical energy entices your senses? Balancing is not easy, but the reward is a peaceful, magical experience when seeking stability through truth. And that was a Chat-tatachán moment Ill never forget. The drum roll of justice.

This was really well done Charlotte. Being born in 1991 (and on the other side of the world) I had only the vaguest knowledge of the 1992 LA riots, and so, for me, this piece was very informative and eye-opening. I didn’t realise how large of an incident this was. And the way you conveyed its gravity was measured and sincere. A great read :)

Nice work. 😎

His history remains a contemporary event. King says, “Why can’t we all just get along”? A message likely more vivid now than ever before.